28 Nov In the Land of Gold: Reflecting on an Era of Japanese Contemporary Art

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/insights/hiroshima-museum-of-art-zipangu/

At Hiroshima Museum of Art, a group exhibition offers a fascinating insight into the past 35 years of Japanese visual expression.

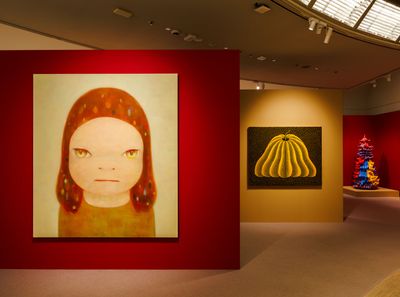

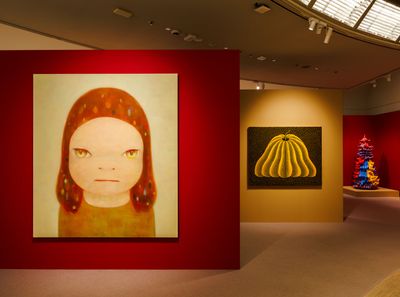

Left to right: Yoshitomo Nara, Yayoi Kusama. Exhibition view: ZIPANGU—Contemporary artists who have run through the Heisei era, Hiroshima Museum of Art (2 November–22 December 2024). Courtesy Hiroshima Museum of Art.

‘Japan is always being “discovered” by other countries,’ says Sueo Mizuma. The Tokyo-based gallerist, who organised ZIPANGU—Contemporary artists who have run through the Heisei era, refers to the combination of cultural admiration and mercenary interest which drove foreign powers to seek out Japan’s treasures. Zipangu was Marco Polo’s term for the country, known at the time as ‘a land of gold’, and underscores other nations’ centuries-old fascination with Japan. Heisei, on the other hand, pertains to Emperor Akihito’s reign, from his ascent to the throne in 1989 to his abdication in 2019.

Miwa Komatsu, See No Evil – Yamainu (2022). Collection of FUDO Co., Ltd. © Miwa Komatsu. Exhibition view: ZIPANGU—Contemporary artists who have run through the Heisei era, Hiroshima Museum of Art (2 November–22 December 2024). Courtesy Hiroshima Museum of Art.

Presenting 29 Japanese contemporary artists and groups selected by Mizuma, ZIPANGU is an attempt to rebrand the so-called lost decades of economic malaise as a period of cultural and creative richness. In addition to superstars like Yayoi Kusama, Takashi Murakami, and Yoshitomo Nara, the exhibition features artists who, while not as well known internationally, are nonetheless pivotal to the era, including Tatsuo Miyajima and Chiharu Shiota, along with younger artists of the nascent Reiwa era, such as Namonaki Sanemasa, teamLab, and Kazuki Umezawa.

It is the second leg of a two-part touring exhibition that started in August at Saga Prefectural Art Museum on the southern island of Kyushu. The history of the show extends back to 2011, however, when it was initially displayed in department stores and regional museums as a way to, as Mizuma describes, ‘heal and rejuvenate Japan through the power of art’ after the Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent nuclear meltdown.

teamLab, United, Fragmented, Repeated and Impermanent World (2013). Eight-channel interactive digital work, endless. Sound: Hideaki Takahashi. Courtesy © teamLab.

Noting that the Heisei era, for Japan, was ‘a peaceful time without war’, Mizuma observes: ‘Exhibiting in Hiroshima naturally encourages reflection on the horrors of war and the importance of peace.’

Many of the works on display speak to this sentiment. Masahiro Usami’s photograph Hayashi Yuriko, Hiroshima 2014 (2014) is a bisected image with representations of colour and life on one side and death and destruction on the other, showing 500 Hiroshima citizens taking part in a ‘die-in’ event for preserving the memory of Hiroshima. Within a mandala-like formation, hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor) Yuriko Hayashi sits at the centre of the scene, wearing a black ceremonial kimono and holding an infant. Surrounded by participants from four generations, the work represents the past, present, and future of Hiroshima.

Makoto Aida, Ash Color Mountains (2009–2011). Acrylic on canvas. 300 × 700 cm. Taguchi Art Collection/Taguchi Art Foundation. ©︎ Makoto Aida. Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery. Photo: Miyajima Kei Cooperation: Watanabe Atsushi.

Two adjacent paintings by Makoto Aida symbolise the histories of both the Heisei era and the city of Hiroshima. Ash Color Mountains (2009–2011), one of Aida’s best-known works, presents a mountainscape composed of thousands of salarymen who appear to be deceased (or, at least, unconscious or intoxicated). This unsettling picture is a scathing commentary on Japan’s modernization, the hypercompetitiveness of the Ron-Yasu global economy, and the aftermath of the burst of the asset bubble in the early 90s, with echoes of Lehman Shock in 2008.

Meanwhile, Aida’s No One Knows the Title (War Picture Returns) (1996) depicts the Parthenon and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) merged together on a multi-panel folding screen. The work critiques Western civilisation as a continuum, from its origins in ancient Greece through to the development of the atomic bomb.

Manabu Ikeda, Rebirth (2013–2016). Pen, acrylic ink, and transparent watercolour on paper, mounted on board. 300 x 400 cm. Digital Archive: Toppan Printing Co., Ltd. Collection of Saga Prefectural Art Museum. © IKEDA Manabu. Courtesy Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo/Singapore.

Among the show’s standout pieces are the astonishingly intricate pen drawings of Manabu Ikeda. Foretoken (2008), the maximalist style of which inspired Daniel Kwan’s 2022 film Everything Everywhere All at Once, shows a Hokusai-esque tidal wave, formed almost entirely of debris, uncannily foreshadowing the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. Similarly, Ikeda’s Rebirth (2013–2016) depicts a gnarled cherry tree under siege of waves in aggregate, within which are contained countless worlds of ruin and regeneration.

No less effusive and evocative of primaeval forces are the works of Miwa Komatsu. Her paintings and ceramics reflect an interest in mythology shared by many Japanese artists who came of age in the Heisei era, including Tomiyuki Kaneko and Ellie Okamoto.

Miwa Komatsu, The Time of Spirits (2024). Acrylic on canvas. 259 x 259 cm. Collection of FUDO Co., Ltd. © Miwa Komatsu.

Komatsu’s central motif is the Divine Spirit. One of its manifestations, the komainu (lion-dog), is said to protect sacred spaces and ward off evil. The Time of Spirits (2024) features them, as do her other works in the show, which draw on a spiritual creativity that Mizuma describes as ‘inimitable by A.I.’ The Day the Earth Shed Tears: Prayers for Peace Spreading from Hiroshima (2022), a painting inhabited by a pair of komainu, was created over a period of more than a year through dialogues with atomic bomb survivors.

‘From hibakusha, I learned the importance of keeping our prayers for peace alive. What happened in Hiroshima affected not only this city, but the entire global ecosystem. The war may be over, but the psychological scars remain,’ Komatsu tells me.

Takahiro Iwasaki, Reflection Model (Rashomon Effect) (2015). Japanese Cypress, plywood, Chinese ink, wire. 180 × 185 × 90 cm. Storehouse of JIT Group Co., Ltd. ©︎ Takahiro Iwasaki. Courtesy ANOMALY. Photo: Keizo Kioku.

Some of the strongest works of Japanese contemporary art are rooted in the past, as demonstrated by ZIPANGU‘s pairing of Reflection Model (Rashomon Effect) (2015) by Takahiro Iwasaki with untitled (2023) by Junichi Mori. Hiroshima native Iwasaki reconstructed the ancient Kyoto city gate, depicted most famously in Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashomon (1950), as a parallel structure in which top and bottom parts are mirror images, like a reflection in water. Iwasaki has made several similar sculptures paying homage to Japanese architectural sites, blurring the lines between reality and illusion, this world and the beyond.

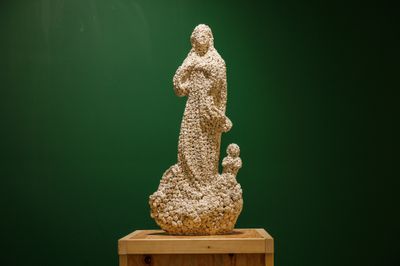

Junichi Mori, untitled (2023). Lithothamnium, resin. 102.5 x 45 x 33 cm. Exhibition view: ZIPANGU—Contemporary artists who have run through the Heisei era, Hiroshima Museum of Art (2 November–22 December 2024).

Gazing out on Reflection Model (Rashomon Effect) is Mori’s untitled, a Madonna and Child sculpture modelled after one from the Urakami Cathedral in Nagasaki that was destroyed by the atomic bomb. This sculpture is made of Lithothamnium, an algae found in the waters off the artist’s home prefecture of Nagasaki, which turns bone-white in colour when exposed to air. The faceless forms of mother and child appear to have mysteriously drifted ashore, like pieces of hallowed debris washed up from the wreckage of history.

Exhibition view: ZIPANGU—Contemporary artists who have run through the Heisei era, Hiroshima Museum of Art (2 November–22 December 2024). Courtesy Hiroshima Museum of Art.

When asked if he felt the first edition of ZIPANGU had achieved its goal, Mizuma replied: ‘Given the scale of [the 2011 earthquake], it is difficult to say whether the exhibition succeeded in uplifting the Japanese people. However, if it managed to provide some sense of vitality to those who attended, I would consider it a success.’ He also noted that in the northeastern Tōhoku region, which was most severely impacted by the disasters, visitors reacted enthusiastically to seeing Japanese contemporary art, whereas, previously, the local museums had mostly displayed pre-Heisei and Western works.

This time, ZIPANGU has a broader vision: showcasing contemporary Japanese art not just for Japanese people but for a global audience as well: Mizuma explains that he hopes to further enhance the exhibition’s content and eventually tour it to leading museums abroad. The Hiroshima iteration serves as a bridge between these domestic and global ambitions. —[O]

ZIPANGU—Contemporary artists who have run through the Heisei era is on view at Hiroshima Museum of Art until 22 December 2024.

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/insights/hiroshima-museum-of-art-zipangu/