13 Nov If God Is a Machine, Then What’s the Motor?

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/features/riar-rizaldi-if-god-is-a-machine/

Ocula meets with the Indonesian artist and filmmaker Riar Rizaldi at his first U.K. solo show at Gasworks, London.

I’ve seen pictures on the internet of Riar Rizaldi wearing assorted cult fan tees—Hong Kong sci-fi film The Oily Maniac (1976); action-comedy The Cannonball Run (1981); R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps (1992–97). When we meet at Gasworks in south London, he’s wearing a brown corduroy baseball cap embroidered with the words ‘IN FILM WE TRUST’ in capital letters, and a lime green Return of the Living Dead t-shirt which reads, ‘They’re back from the grave and ready to party!’

Rizaldi’s sartorial harking back to 1980s and ’90s culture manifests not only in his attire, but also in his filmmaking and artistic practice. ‘I’m always interested in things that I encountered when I was a kid,’ he tells me. ‘I grew up with a mixed entertainment and pop culture. The way I see Western entertainment, or Western cultural products, is a bastardised version. At the same time, I grew up with a lot of ghost stories from Indonesia.’

Riar Rizaldi. Photo: Dan Weill.

He recounts watching ’80s American horror movies as a child at the itinerant outdoor makeshift cinema in the city of Bandung, where he was born and raised. Screened without subtitles, the films would be translated live in Indonesian and Sundanese through a microphone. As a result, Rizaldi distinctly remembers Halloween—the 1978 slasher directed by John Carpenter—as a romance.

‘The translator told a different story,’ the artist recalls. ‘He didn’t understand English, so he made it up. I still remember Halloween as a story about Michael Myers being in a mental asylum, trying to find his love. When I understood English, I realised it was a completely different film. But my first encounter was that mistranslation.’

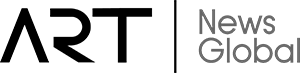

Riar Rizaldi, Mirage – Metanoia (Prelude) (2023) (still). Single-channel video, 3:2, colour, stereo sound. 6 min, 4 sec. Courtesy the artist.

These contrasts and mistranslations feed tangibly into Rizaldi’s show at Gasworks. Comprising two films, a tiled floor, a series of drawings, and a publication, Mirage (3 October–22 December 2024) proposes a speculative dialogue about the intersections of modern science and technology with Sufi mysticism, a movement that once flourished in the Indo-Malay archipelago. He explains: ‘The root of Islam in Indonesia is Sufi mysticism but, in the 14th and 15th centuries, it was marginalised because there was this emerging of Islamic Sultanates, which is now established and institutionalised. Sufi mystics, on the other hand, were wandering people who were against institutions; they were connected to a very different way of understanding reality.’

Exhibition view: Riar Rizaldi, Mirage, Gasworks, London (3 October–22 December 2024). Commissioned and produced by Gasworks. Photo: Dan Weill.

One Sufi figure Rizaldi references is the 16th-century writer Hamzah Fansuri, whose theories are the main subject of discussion between an enigmatic pair of futuristic characters—’kosmoloogs’—in his six-minute animated film, Mirage – Metanoia (Prelude) (2023). ‘Fansuri thought that God was located in the smallest particle; that we didn’t see God, because God is located in the atom,’ Rizaldi explains.

It’s with this level of granularity that Rizaldi underscores peripheral and pluralistic theories of existence. In Metanoia, the kosmoloogs drift across the Milky Way, prospecting this concept along with other existential musings on Sufi atomism. ‘If God is a machine, then what’s the motor?’ one asks, to which the other responds: ‘Thermodynamics, entropy, and, of course, our consciousness.’

Riar Rizaldi, Mirage – Metanoia (Prelude) (2023) (still). Single-channel video, 3:2, colour, stereo sound. 6 min, 4 sec. Courtesy the artist.

The animation style mimics that of American production house Hanna-Barbera, who created The Jetsons—the futuristic cartoon released in 1962, the year after the Soviet Union sent the first person into space—while the subtitles are in a distinctly Disney-style typeface. ‘Disney was the first company to make cartoons for children about the future of science,’ Rizaldi says. ‘And The Jetsons was one of the first series to draw a lot from scientific speculation. Each episode is all about a different aspect of scientific discovery. There’s one episode about flying cars—that’s how flying cars became popular, because of these cartoons. Before, it was a very marginal idea.’

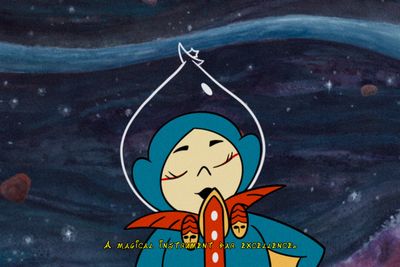

Riar Rizaldi, Mirage – Eigenstate (2024) (still). Single-channel video, 3:2, colour, stereo sound. 29 min, 54 sec. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Riskya Duavania.

Rizaldi’s research into Sufi mysticism developed in parallel to his 2022 artist residency at CERN, a Swiss centre for nuclear research, where he learned about particle physics and quantum mechanics. ‘They have this large collider where they mix atoms,’ he says. Abstract renders of these atoms—in the form of flashing, orbiting circles—appear intermittently, like circuit breakers, in Rizaldi’s second film, the half-hour live action Mirage – Eigenstate (2024).

Riar Rizaldi, Mirage – Eigenstate (2024) (still). Single-channel video, 3:2, colour, stereo sound. 29 min, 54 sec. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Riskya Duavania.

One of the first scenes in Eigenstate is set in the foothills of Mount Merapi, an active volcano in the province of Central Java where Rizaldi lives. Amid the craggy terrain, a TV presenter—played by actor Hannah Al Rashid—holds a microphone and recounts in Indonesian, with English subtitles, a parable about Nasruddin, a character in Muslim folklore, who is looking for a lost key. The reportage style is derived from BBC science documentaries and Carl Sagan’s Cosmos (1980–81), in its time an inventive educational series where Sagan explores the origins of the universe, extraterrestrial life forms, and space exploration, among other ideas. ‘But in this film, I try to make it more like science fiction, with different characters,’ Rizaldi says. ‘That’s an idea that I want to appropriate—that science communication is not necessarily something you read in a journal, but is transmitted through popular culture.’

Exhibition view: Riar Rizaldi, Mirage, Gasworks, London (3 October–22 December 2024). Commissioned and produced by Gasworks. Photo: Dan Weill.

The pale, multicoloured, matte geometric tiles that cover the floor of the room in which Eigenstate screens are made of compacted volcanic ash from the Merapi mountains. ‘We shipped like a thousand kilograms of tiles,’ Rizaldi laughs. ‘There are around two thousand pieces, which are very fragile. We can’t fire them.’ Walking upon them feels akin to stepping onto another planet, something that is depicted in the second scene of Eigenstate, where Al Rashid, emerging from a crashed, minaret-shaped spaceship on unknown terrain, monologues about monotheism and Sufi atom theory. She digs into the sandy ground with her hands, until she reaches far enough below that a green liquid begins flowing from the cavity. ‘In the desert there are only ghosts and mirages,’ she says.

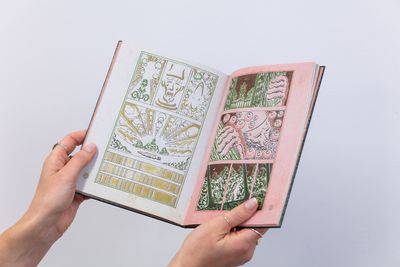

Comics are another cultural product that have infiltrated Mirage, with Marvel’s Doctor Strange a primary source of inspiration for Rizaldi’s slim hardcover comic, Mirage – Theophany (2024), accompanying the exhibition.

Riar Rizaldi, Mirage: Theophany (2024). Illustrated by Arda Awigarda. Commissioned by Gasworks as part of the exhibition Mirage (3 October–22 December 2024). Courtesy the artist and Gasworks.

‘For a long time, Marvel made comics based on science,’ he explains. ‘Captain America got his powers from this biological serum; Iron Man is this technocratic guy, and then, all of sudden, in the late sixties—maybe because of the hippie movement, psychedelics, et cetera—they look more to Eastern philosophy and an Eastern understanding of the world.’

‘Doctor Strange is a surgeon who’s in a car crash. He then travels to the Himalayas to meet this master guru, and suddenly he goes into these different dimensions. It’s a bastardised version of Eastern mysticism, which I find funny and ironic, but also aesthetically fascinating. I’m interested in these mutations as the cultural product of these pluralistic world views.’ —[O]

Riar Rizaldi: Mirage is on view at Gasworks, London, until 22 December 2024. On 16–17 November, Gasworks will host the symposium Strangelet in tandem with Rizaldi’s exhibition.

Mirage: Eigenstate is screening as part of Singapore International Film Festival on 8 December 2024.

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/features/riar-rizaldi-if-god-is-a-machine/