15 Oct Hew Locke Shares Curiosities from the British Museum

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/insights/hew-locke-shares-british-museum-curiosities/

Locke spent two years delving through the Museum’s collection—examining artefacts the British Empire brought back from Africa, India, and the Caribbean—in preparation for his new show.

Hew Locke, The Watchers at the British Museum, 2024. Photo: Richard Cannon.

Guyanese-British artist Hew Locke is presenting specially commissioned works at the British Museum for the exhibition Hew Locke: what have we here?, which opens in London on 17 October.

These include a Parian ware bust of Queen Victoria in regalia that includes skulls and tropical foliage, an acrylic portrait of musicians on a bond certificate issued by the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and The Watchers—carnivalesque figures that look back at museum goers, breaking the fourth wall like a Greek chorus.

In anticipation of the opening, Locke shared four items in the Museum’s collection that helped inspire him, along with one of his own creations.

Barbados Penny, England (1788). Copper alloy. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Barbados Penny

In 1788, the so-called Barbados or Slave Penny was struck by a planter for use on the island. On one side is the head of an African man with a feather crown. This references the feather crowns of Amerindians, as well as heraldic ostrich feathers of the Prince of Wales. Around it is the Prince’s motto ‘I serve’. It’s a sick joke, basically, emphasising the servitude of the enslaved man, as opposed to the willing service of the prince to his people.

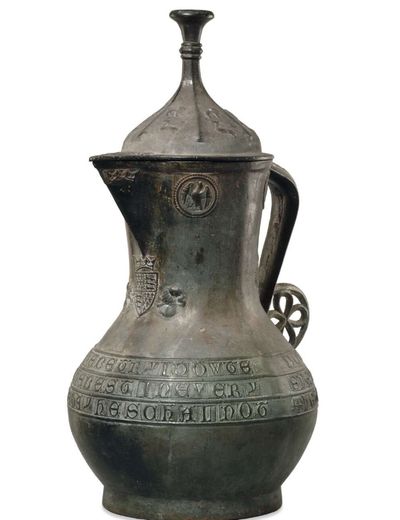

Unrecorded English artist, so-called Asante Jug (1390s). Bronze. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Asante Jug

What’s this ewer doing in Africa? It was made in the 1390s, possibly for King Richard II, and travelled from England to the Asante royal court in modern day, maybe traded or as a diplomatic gift. We can speculate on how it got to the Asante court, but we know that it did get there, and that it was a prized object. Thinking about how foreign objects, such as the Koh-i-noor diamond, become symbols of British power—here, in a mirrored way, European objects became a symbol of African power. The British looting it in 1896 could be seen as the return of a ‘long term loan’!

Maria Sibylla Merian, Toucan eating a small bird (c. 1701–1705). Watercolour and bodycolour on vellum. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Toucan Eating A Small Bird

Artist Maria Sibylla Merian and her daughter voyaged to Suriname in 1699. They drew heavily on the local knowledge and assistance of Indigenous and enslaved people who laboured under horrifying conditions on Dutch sugar plantations. [Their works] seem to be made up of many different studies from life but also stories that have been told to her: ‘This bird did this. I once saw a toucan eating a bird.’ To me, the images are metaphors for the violence that was going on there—the crocodile eating the snake, the toucan eating the bird. They must have witnessed the extremes of punishment. It doesn’t take a psychologist to examine this work and see it as a metaphor—well I think so anyway.

Unrecorded Asante artist, Ghana, gold pendant (1850–1873) and R & S Garrard & Co, London, silver-gilt dish (1874). © Trustees of the British Museum.

Pendant / Dish

The centre of this plate is a pendant belonging to a soul priest. Similar discs were used by members of the Asantehene’s court in rituals that purified and replenished the King’s vital powers. Looted during the Third Anglo-Asante war, the disc was set in a silver-gilt plate by the jeweller Garrard & Co in 1874. It looks like a European object; the aesthetic of the original Asante object has been trapped in the European design. Its function is ignored, it’s trapped and killed, it becomes just a trophy.

Hew Locke, Armada 6 (2019). Mixed media. Hales Gallery, London © Hew Locke. Courtesy Ikon Gallery. Photo: Stuart Whipps.

Armada 6

Boats symbolise many things—power, adventure, trade, war, our journey through life. They symbolise flows of goods and ideas, as well as people. Armada 6 is based loosely on the American boat the USS Constitution. It fought against the British and protected American trade, including the slave trade. But later it was used to disrupt the slave trade. It is adorned with fake gold Queen Idia masks from Benin—a symbol of African culture. The mercenary represents what someone is fleeing from when they get in a precarious boat to cross the Mediterranean—a generic man with a gun to escape from. And there are skeletons, known as Memento Mori—a reminder of the fragility of life. —[O]

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/insights/hew-locke-shares-british-museum-curiosities/