23 Jun Glenn Ligon and Thelma Golden on James Baldwin

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/glenn-ligon-and-thelma-golden-on-james-baldwin/

On the occasion of his eponymously titled show at Hauser & Wirth, held earlier this year in Hong Kong, the artist met with Thelma Golden, director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, to discuss Baldwin and his impact on Ligon’s practice.

Ligon and Golden are long-time friends widely recognised for their influence on contemporary art. Individually, they have both been featured in ArtReview‘s Power 100, and Golden was included on the 2024 Time 100 list. Together, they coined the term ‘post-black art’ to refer to a post-Civil Rights generation of African American artists and have collaborated on various other important projects. In 2001, for example, Golden curated Ligon’s solo exhibition, Stranger, at the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, which included eight of his ‘coal-dust’ paintings from his ‘Stranger’ series (1997–ongoing).

Glenn Ligon with Thelma Golden during talk at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong (25 March 2024). Photo: Anna Dickie.

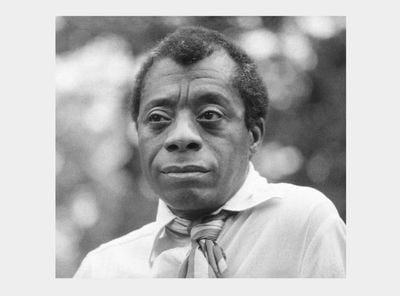

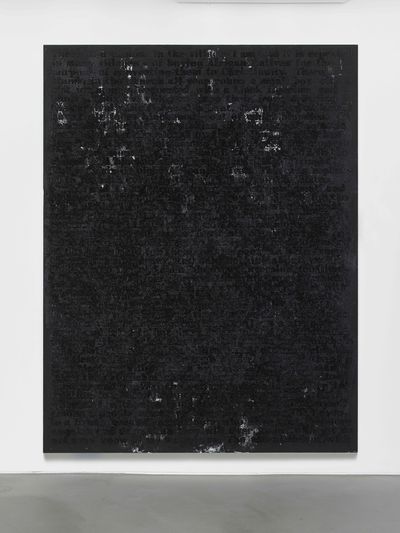

The Hong Kong exhibition presented three new ‘Stranger’ paintings, as well as a new abstract series, ‘Static’ (2023–ongoing), and a selection of untitled drawings on kozo paper (all 2023). All monochromatic, the works first appear to be Minimalist abstractions. On closer inspection, however, excerpts from Baldwin’s ‘Stranger in the Village’ can be discerned. The text recounts the writer’s experience of living in the small Swiss mountain village of Leukerbad, where villagers reacted to him with curiosity, and sometimes fear.

The ‘Stranger’ paintings comprise stencilled text from the essay applied to large canvases with oil stick, creating a relief composed of near-illegible sentences. As the artist moves the stencil across the canvas, oil stick residues smudge and obscure parts of the writing. Ligon further abstracts the text by coating the surface with coal dust—a black, gravel-like waste product of coal mining—which glimmers in the sunlight.

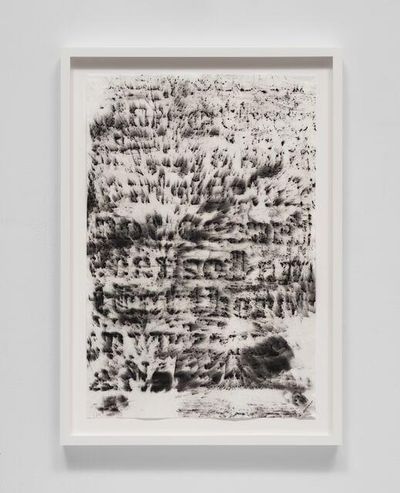

Taking the abstraction of language further, Ligon produces his untitled works on paper by layering kozo paper above one of his ‘Stranger’ paintings. Then, the blurred text is transferred from the painting to the paper by rubbing carbon graphite across it.

Exhibition view: Glenn Ligon, Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong (25 March–11 May 2024). Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: JJYPHOTO.

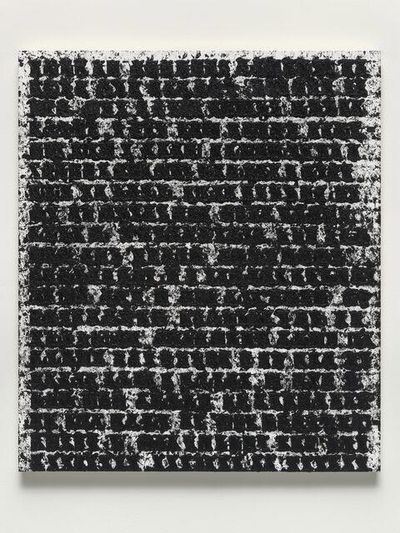

In contrast to the ‘Stranger’ series, the new ‘Static’ paintings mark a departure in process. Ligon stencils excerpts from Baldwin’s text in white oil stick onto a white gesso ground, subsequently rubbing black oil stick onto the raised areas in a frottage process. The artist sees the resulting compositions as visual echoes of the television static he experienced as a child when the transmission signal was interrupted or turned off. Blending text and abstraction, Ligon explores ideas around race and culture, whilst also ruminating on the meaning of texts like Baldwin’s that morph with the changing times.

The following is an edited transcript of Golden and Ligon’s discussion—held at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, on 25 March 2024—published with the permission of both.

Glenn Ligon, Stranger #96 (2023). Oil stick, etching ink, coal dust, acrylic and pencil on canvas. 289.6 x 223.5 cm / 114 x 88 in. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist; Hauser & Wirth, New York; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Thomas Dane Gallery, London; and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Ronald Amstutz.

TGThis exhibition brings together a body of work that focuses on James Baldwin’s essay ‘Stranger in the Village’, a text that you have been working with, in, and around for as long as we have known each other. Can you discuss how text—as image, as form—has informed your work?

GLIn college, I was very interested in Abstract Expressionism—Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Yves Klein—folks like that. I wanted to be an abstract painter and realised there was a gap between the work I was interested in and the work I was making.

After approximately ten years of making second-rate abstract paintings, I changed the practice to incorporate text from essays and novels that I was reading directly into paintings. The text became a way of introducing new content into the space of painting.

I also looked at painters who use text, like Jasper Johns, and conceptual practices like that of Barbara Kruger or Joseph Kosuth, who use text to introduce a different kind of content to painting.

Exhibition view: Glenn Ligon, Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong (25 March–11 May 2024). Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: JJYPHOTO.

TGWhy was content important to you?

GLIt’s a story I often tell. When I took part in the Whitney Museum‘s Independent Study Program around 1985, we read very dense, theoretical texts, like French psychoanalytic texts by Michel Foucault. I mentioned to an artist in the programme that I had been reading James Baldwin. She said, ‘James Baldwin?’. She had never heard his name.

And I thought, well, there is a problem here. Maybe my task is to introduce names like James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, or Zora Neale Hurston into the space and to a painting practice. This way, when you walk into a gallery, you must deal with them as figures, and with their ideas in the work.

TGThis move to embrace content was clearly about what was in those essays, what those writers wrote about—the reflections on culture, how they allowed a way to consider a wider realm of critical theory and writing then. How did you first think about putting text on the canvas itself?

GLOh, quite literally! The best things that happen in my work come from mistakes. When I started working with text, I wanted to paint very clear, perfect text. But I was using letter stencils and oil stick. Oil paint doesn’t want to be used to create clear, crisp letters. I had to embrace the kind of messiness and text disappearing into the painting, and this became one of the central ideas behind all my work—this back and forth between legibility and abstraction, being able and unable to read something.

TGNumerous texts have informed your work, but ‘Stranger in the Village’ is central. This is an essay that was published in Harper’s Magazine in 1953, written by Baldwin a few years after he left Paris and began to spend time in Switzerland because his partner was from a village there.

How did you come upon Baldwin’s work? What about this essay was intriguing to you?

GLI went to Wesleyan University, in Connecticut, U.S., and in the African American literature course taught by Robert O’Meally (whom we both know and is now at Columbia University), James Baldwin was one of the authors we read. We read his novels, which he was arguably more famous for then.

But I loved his essays because they were panoramic: a ten-page essay will discuss Baldwin’s relationship as an African American to European culture and his relationship to Africa as an African American living in Europe. He left America to take a break from American racism. It was the 1950s and he was aware of Europe’s colonies in Africa. He thought about that relationship and his relationship to America. He was thinking through big issues. I was very drawn to his essays because of that.

The best things that happen in my work come from mistakes.

‘Stranger in the Village’ is the essay I have used the most. When I first started using the essay in the mid-1990s, Baldwin was not well known. Today, there are films about him and he is quoted often.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, he was considered a spokesperson for Black Americans. He was very famous; he knew about Malcolm X and knew Martin Luther King. But by the 1990s, he fell a bit out of favour. Baldwin’s words were not as present in the culture as they are now, so the essay—which is from 1953—remains something I can return to repeatedly and find new meaning in, thinking about how it relates to where we find ourselves now.

When you are making a painting, you put a white gesso ground on the canvas and paint on top of it. Baldwin’s essay, in some ways, is the ground on which I paint. I start with the text. It is the blank canvas. That’s my relationship to that text now.

Glenn Ligon, Stranger (Full Text) #1 (2020–2021). Oil stick, gesso, and coal dust on canvas, two panels. 120 x 540 inches (304.8 x 1371.6 cm). © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jon Etter.

TGYou have read this essay hundreds of times and painted the words numerous times too. How Baldwin is understood has shifted. He has become a voice that many people are now seeking for its wisdom. How has your sense of the essay’s meaning changed? How has that impacted your work?

GLMy relationship to the essay has changed. I have been thinking about how other artists and writers position James Baldwin in their work. For example, Teju Cole—a beautiful writer—wrote the essay ‘Black Body’ (2016) about going to the tiny Swiss village where Baldwin lived in 1953.

Cole, who grew up partially in the United States and partially in Nigeria, goes there as an African American. He says that in some ways, there is a continuity between the village where Baldwin lived and the one he finds himself in, but there is also discontinuity.

As he says, ‘Yes, people look at me when I enter the restaurant in the hotel, but Beyoncé’s on the radio.’ So there is the sense of Black American culture being everywhere, or particularly Black American music being representative not only of Black culture, but American culture.

Exhibition view: Glenn Ligon, First Contact, Hauser & Wirth, Zürich (17 September–23 December 2021). © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jon Etter.

Baldwin literally says, ‘For some of the villagers here, I’m the first Black person they’ve ever seen.’ But he also says, ‘They think I must be from Africa because for them, America is white.’ They can’t imagine he’s American because Black people are not from America. What I really love about Cole’s essay is that he is in some ways critical of Baldwin—of how Baldwin discusses Africa in that essay. I like this sort of looking back and reevaluating a text from generation to generation.

Baldwin’s words were not as present in the culture as they are now, so the essay—which is from 1953—remains something that I can return to repeatedly and find new meaning in it

I think the big shift recently is that I made paintings using the entire essay. The first one [Stranger, Full Text #1, 2020–2021], was shown at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich in 2021 [Glenn Ligon: First Contact]. The difference between using a fragment of Baldwin’s essay and the entire text is that the text then also becomes panoramic.

Like a landscape, it’s so long you can’t take it in all at once. It becomes as though you are looking at the atmosphere or weather, or a sort of diorama. There is a feeling of enormity to the work, which reflects the enormity of Baldwin’s topics in this essay. But again, it took me 20 years to have the space, time, and stamina to make a 45-foot-long, 10-foot-high painting.

TGCould you tell us about the new ‘Stranger’ paintings?

GLIn these paintings, you can see a piece of Baldwin’s essay ‘Stranger in the Village’ stencilled in white, black, and brown. I stencil the letter first in oil stick, one letter at a time, starting at the top and going to the bottom.

While the oil stick is wet, I put coal dust on top. The coal dust is wastage from coal mining. It comes in big, 100-pound bags, and it looks like a shiny black growl. I was drawn to it as a material because it is a waste product, and because Baldwin often in his essays discusses what it means to write from the margins of a society rather than the centre.

Glenn Ligon, Stranger #98 (2023). Oil stick, silkscreen, coal dust, acrylic and pencil on canvas. 289.6 x 223.5 cm / 114 x 88 in. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist; Hauser & Wirth, New York; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Thomas Dane Gallery, London; and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: JJYPHOTO.

TGWhen did you start using coal dust?

GLProbably in 1997, and I think the first works I did didn’t have text to them. They just used the material. I was so fascinated with it as a material. And then I started introducing Baldwin’s text.

Baldwin would say that the margins of society are the places where people are treated with the least respect and esteem—that you need to look more carefully because they will tell you what the society is. And Baldwin identified with and thought and wrote from that place a lot.

I like this sort of looking back and re-evaluating a text from generation to generation.

In some ways, Baldwin is at the centre of American society. However, despite his enormous fame, he still served as a spokesperson for people on the fringes. The coal, being this kind of waste product elevated into the space of a painting, seemed to be a nice parallel to the themes in Baldwin’s essay.

In addition, Baldwin wrote with such density. The coal dust also gives the paintings a kind of density and weight. Baldwin was a child preacher and very much of the church in some ways, although he broke with religion early on. If you consider his writing, he uses very elaborate sentences. This also grew partially out of his love of people like Henry James, the American writer.

TGAt what point did you start working monochromatically properly?

GLThe white painting in the back is quite new. I was interested in just using paint to make the text and seeing how that would read. It’s much clearer in that painting with coal dust.

Using just paint does an interesting thing. It adds weight and density to the paintings, but it also makes them very difficult to read. Maybe I was thinking of the mountain village in Switzerland where Baldwin writes this essay, surrounded by snow and ice as far as the eye can see. I also thought about the history of white-on-white abstraction. The layering of the text is very apparent in the painting. To build up this much paint in a painting, you can see it—that sort of density.

Glenn Ligon, Static #8 (2023). Oil stick, coal dust and gesso on canvas. 170.2 x 129.5 cm / 67 x 51 in. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist; Hauser & Wirth, New York; Regen Projects, Los Angeles; Thomas Dane Gallery, London; and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Ronald Amstutz.

TGYou’ve said that you began as an abstract painter and in many ways became an abstract painter again. And the ‘Static’ works are your latest move into thinking about abstract languages. Can you talk about these new works?

GLThe paintings start with Baldwin’s text on which I rub a black oil stick, which produces a static noise, and they look like static to me. I remember telling Luca, my ten-year-old godson, about static and realised I had to explain static to him because he lives in a digital world.

When I was a kid, TV stations went off the air at one in the morning. They played the national anthem and the screen went blank, except for this grey pattern. I imagine when you used to have to turn the dial on the radio in between stations, the noise that you hear—that’s static.

I was thinking about that in relation to Baldwin’s text and someone said, static is the sound of being in-between something. I thought, ‘That’s it.’ In a way, that’s where we are, at least in the American context, as a culture. We do not quite know what we are in-between, or what is coming. We cannot totally rely on the past as a guidepost to predict the future.

Glenn Ligon, Static #10 (2024). Oil stick and gesso on canvas. 67 x 51 inches / 170.2 x 129.5 cm. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ronald Amstutz.

It feels like we are in an in-between place with language. I always say about these paintings, part of what they are about is language collapsing, failing, and being unable to communicate. But then I was just reading an interview with American theorist Judith Butler, and she discusses the banning of books in the United States and banning of certain words and language. And she says, ‘In a very uncertain world, people focus on language because they think they can control language.’

I feel like language is failing, but she is saying, no, language has a lot of power and that is why they’re banning books or prohibiting words. I feel like we are in this very static, in-between moment, and for me that is what these paintings are about. But they are also about me becoming more of an abstract painter—in some ways, going back to my roots.

Glenn Ligon, Untitled #24 (2024). Carbon and graphite on Kozo paper. 18 x 12 inches / 45.7 x 30.5 cm. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Thomas Barratt.

TGDid you know that’s where you were going?

GLNo, as I mentioned earlier, often my work starts with some mistake. My first white-on-white painting didn’t work. It sat in my studio for a good five to six years. Then I thought, well, it already does not work, so I’m not going to make it worse. Why don’t I try just rubbing on top of it?

The moment something is forgotten is often the moment to look at it closely again.

That was the first thing where it’s just like, ‘Oh, the thing that didn’t work now works because I’ve added something to it. That is interesting.’ I guess the lesson there is throw nothing out if you’re an artist. It may take you a long time, but the failures teach you something.

TGWell, I think you’ve always learned from your work. You have always spent a lot of time thinking about how you make and learn from different bodies of work.

GLI think art-making is a way of thinking, so I don’t make paintings based on having an idea that must look a certain way. I just make it. Often, I discover things while making the work, but years later realise, ‘Oh, that’s what that was about.’ And I go back to those works to go forward.

TGCan you talk about the place of drawing in your practice, and within this body of work?

GLI don’t make that many drawings, relatively speaking. When I do, they tend to be in long series. Years ago, a friend went to the Baoshan Steel Park in Shanghai, where there are these stones with carvings. From the gift shop, he sent me a rubbing off one of these stones.

I looked at it fascinated and thought, how can I make work using this rubbing technique? I decided to try it. I laid a ‘Stranger’ painting on a table, put down wet kozo paper and rubbed on top of it with graphite and carbon. Now because the paper’s wet, when I draw, the carbon spreads out. In some drawings, the text is clear, others seem like watercolour.

Every drawing in this show is made from the one painting, but they all appear different. I love working serially that way, where you set up a way to make something, but everything you make is different. Maybe that’s a legacy from people like Sol LeWitt. I like setting up a system and letting that system break down in a way to tell me a different way to go.

Glenn Ligon, Redacted #10 (2023). Oil stick and gesso on canvas. 43 x 37 inches / 109.2 x 94 cm. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Ronald Amstutz.

TGFinally, let’s discuss the painting in the window [Redacted #10, 2023]. The space opens out the entire narrative.

GLIt’s from a series called ‘Redacted’ (2023). When I was a student, we had manual typewriters, not computers. When you handed in a paper, you typed it up and if it didn’t have to be perfectly presented, you corrected your mistakes by putting an ‘X’ through the letters.

I was thinking about that redaction—’X-ing’ out something. So underneath those ‘X’s on that painting in the window is this Baldwin text, but X-ed-out by the very thing that makes the text.

Using the letters to erase a text that spades out of letters was interesting to me. But also thinking about the present, where Baldwin is one of those authors in the U.S. whose works are being banned. Thinking that we are past a certain moment and realising we’re not. I guess ‘X-ing’ a text is also taking something back to abstraction. So these are all ways to think about abstraction.

TGAnd is that a primary concern for you at this moment? I am trying to unpack these different ways into abstraction for you.

GLI think it’s always been part of my practice, a deep ingrained love of abstract painting, but always a desire to think about abstraction, plus something—abstraction plus Baldwin, abstraction plus Zora Neale Hurston. So adding this other layer of content into paintings.

Mark Bradford coined the term ‘social abstraction’. I think it’s an interesting way to think about abstract painting as having this political content, but also being deeply invested in the history of abstraction as a painting genre. It’s one of the things I’m thinking about.

Exhibition view: Glenn Ligon, Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong (25 March–11 May 2024). Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: JJYPHOTO.

TGInhabiting abstraction with a different sense of voice and different sense of possibility.

GLYes. When I went to school in the 1980s, we learned about Abstract Expressionists, but nobody mentioned Jack Whitten, who also shows with Hauser and is a painter that I admire deeply. He has a big show coming up in Washington D.C. and New York—I’m writing an essay for the catalogue.

But I had to find out about Whitten as an adult painter. His painting was not on the curriculum when I was in school. The most amazing moment for me was seeing one of his big paintings in the Museum of Modern Art‘s permanent collection and realising I could keep coming back.

In a way, I realised that as an African American, my work is positioned differently within the canon of abstract art. So I am aware and thinking about that, but also thinking about how other artists have dealt with that.

I am also aware that text goes in and out of focus. Baldwin’s work went in and out of culture. Likewise, Zora Neale Hurston was very famous in the United States in the 1920s and 30s. But by the 1960s, 1970s, her work was out of print and she was buried in an unmarked grave.

That kind of back and forth between very present and not present is something I’m super interested in. Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to texts that are from the past, to bring them into the present in various forms. I never met Baldwin, but he’s been so important for me. The moment something is forgotten is often the moment to look at it closely again. —[O]

A new publication ‘Glenn Ligon: Distinguishing Piss from Rain; Writings and Interviews’, edited by James Hoff, will be released by Hauser & Wirth Publishers on 25 June 2024.

Glenn Ligon’s solo exhibition ‘Glenn Ligon: All Over The Place’ will be held at Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, from 20 September 2024 to 2 March 2025.

1 Jason Moran, ‘Glenn Ligon’, Interview, June 8, 2009, unpaginated.

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/glenn-ligon-and-thelma-golden-on-james-baldwin/