28 Nov Claudette Johnson on Power and Self Determination

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/claudette-johnson-on-power-and-self-determination/

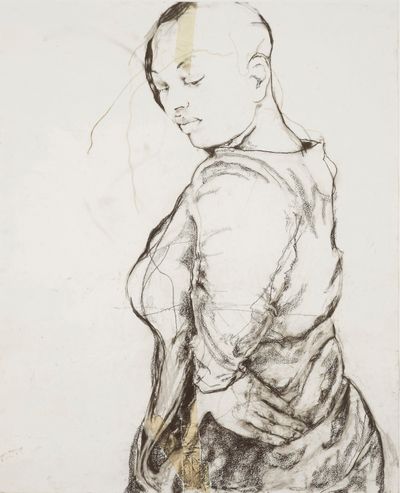

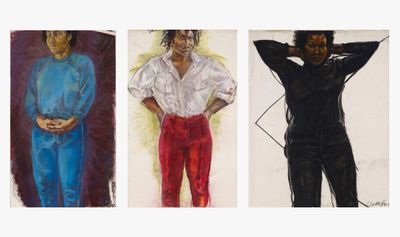

Several years ago, the artist-filmmaker Ayo Akingbade made Claudette’s Star (2019), a short film dedicated to Claudette Johnson. In this filmic ode, Akingbade and her peers discuss Johnson’s work Trilogy (1982–1986) and debate the question of how to create a legacy for those whom canonical art history has so often obscured. Johnson’s influence on a younger generation of artists, many of them Black women like Akingbade, is evident in Claudette’s Star. Johnson inspired them to play with and challenge artistic canons and to create their own spaces.

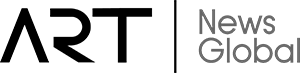

Claudette Johnson, Trilogy (Part One) Woman in Blue; Trilogy (Part Three) Woman in Red; Trilogy (Part Two) Woman in Black (all 1982). Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. Courtesy © Claudette Johnson.

While studying at Wolverhampton School of Art, a precocious Johnson was a key member of the BLK Art Group, which she joined in 1981. The following year, the group organised the First National Black Arts Convention to increase the profile of Black artists across the U.K. Many have recounted a spirited exchange that took place during Johnson’s convention presentation, in which she considered depictions of Black women within Western art history. (Johnson was the only woman to give a talk that day.) Because of the debate, Johnson and a group of fellow female artists, including Lubaina Himid and Sonia Boyce, disbanded earlier than planned to hold a separate gathering.

Blackness and womanhood have long occupied a beleaguered position in the Western canon, where their rare appearances have usually taken the form of racist caricatures, exoticised accessories or oversexualised objects of a leering white gaze. As a challenge to this history, Johnson has made Black female beauty, empowerment and community the fulcrum around which her practice largely revolves. Long before the language of intersectionality became popular, Johnson recognised the importance of her racialised subjectivity and how it could be marginalised in male-dominated discussions about race or in nonblack feminisms.

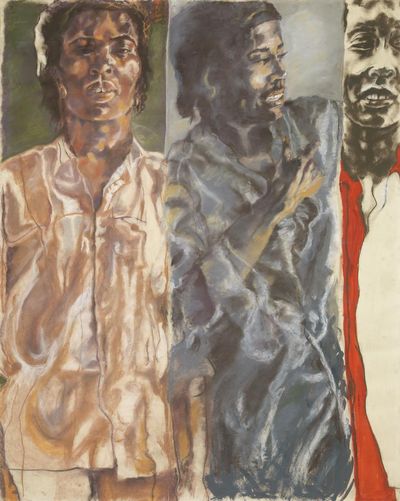

Claudette Johnson, And I Have My Own Business In This Skin (1982). Sheffield Museums. © Claudette Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Modern Art Oxford. Photo: Ben Westoby.

In And I Have My Own Business in This Skin (1982), Johnson staged an encounter with Pablo Picasso, arguably the most emblematic European male modernist, whose legacy is shot through with misogyny and appropriation. Johnson, a self-described fan of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), set out to engage the formal daring of his masterpiece while confronting its problematic relationship to African art and the female form.

In subsequent years, Johnson has returned to Picasso in works such as Three Women (2024), her commission for Art on the Underground at Brixton Station. In the recent triptych, Johnson’s three sitters assume poses taken directly from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon but, as Johnson tells me during our conversation, against the background din of a noisy cafe: ‘When these women adopt those poses, it represents power and self-determination.’

Claudette Johnson, Three Women (2024). Brixton Station. Commissioned by Art on the Underground. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Angus Mill.

The Art on the Underground commission comes after a rush of recognition over the last few years, including two solo exhibitions at Hollybush Gardens, the London gallery that represents Johnson, as well as solo exhibitions at Modern Art Oxford (2019), Ortuzar Projects, New York (2023), and the Courtauld, London (2023)—the last two of which earned her a Turner Prize nomination. This acknowledgement followed two decades of neglect—a period Johnson has referred to as a ‘long wilderness’. These recent, wide-ranging overviews have not only enabled a new audience to become acquainted with her work, but they’ve also allowed those already familiar with Johnson’s practice to revisit earlier pieces and to better trace the breadth and evolution of her oeuvre over the years, including her decision—after becoming a mother to sons—to depict men in her paintings.

Claudette Johnson. Exhibition view: Turner Prize 2024, Tate Britain, London (25 September 2024–16 February 2025). Courtesy Tate. Photo: © Tate Photography/Josh Croll.

Johnson takes on the label of a portrait painter with reluctance, offering her own form of quiet resistance by pushing against the tradition of portraiture in which sitters are contained within the frame and depicted with accoutrements that tell a story about their biography. Her figures are often heavily cropped and placed at strange angles or strike difficult and dynamic poses at odds with their often-impassive expressions. Johnson also places herself at a remove from the kinds of portraiture in which verisimilitude is the goal. Her depictions of historical figures, such as cultural theorist Stuart Hall and abolitionist Sarah Parker Remond, are more imaginative interpretations than straightforward likenesses.

Following the inauguration of Three Women, Johnson and I met to discuss her work. I enquired about the names of the sitters, one of whom I thought I recognised. Johnson confirmed their names reluctantly, before reminding me that she doesn’t think of the work as portraits to which the sitter’s identities are essential. ‘These women are like icons; they transcend who they are as individuals.’ Her main concern is that her sitters convey a sense of power, something which is difficult to deny when standing atop the stairs at Brixton station, their casual air of self-possession given so much space, their gazes fixed intently on the viewer.

TJMHow are you feeling about Three Women, your first public art commission, now that it’s installed in Brixton station and available for all to see?

CJI’m elated about the way the work looks in situ: it’s doing what I hoped it would do. The women are really present and unmissable. So, that’s exciting. I think the contrasting approaches in the work hold their own in that space, as well; they give a sense of transitioning across three different types of womanhood, if you like.

Claudette Johnson, Untitled (1987). Pastel and gouache on paper. 1514 x 1215 mm. Collection of Tate.

TJMThere appears to be a clear conversation between this work and Trilogy, a triptych of Black female figures dressed in blue, black, and red. Can you discuss this practice of self-reference and what inspires it?

CJThree Women does refer to Trilogy but also to Untitled (1987), which is a single work divided into three strips. It’s in the Tate collection and currently on display at Tate Britain. Untitled presents three versions of the same figure, transitioning from a rather dark, reflective figure to a character in motion to a figure with the red strip of clothing underlining that moment of transition. The transitionary moment in Three Women is represented by the central figure in motion, twisting towards us, and drawn very sparely in contrast to the women in blue and white on either side of her.

TJMWhat is it about the triptych format that interests you?

CJI like the journey that the viewer has to make across a series of figures. There is a connection, and there are repeated rhythms. At the same time, it’s a challenge to allow each figure to hold her own space and have her own conversation with the audience.

Claudette Johnson with Three Women (2024) at Brixton Station. Commissioned by Art on the Underground. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Angus Mill.

TJMWhen were you commissioned to do the work for Art on the Underground, and how long have you been working on it?

CJI agreed to the Art on the Underground commission and then I was nominated for the Turner Prize, so I was working on both at the same time, which was quite a bit of pressure.

I had already decided on two of the sitters for Three Women, but the third sitter took a while to confirm. At one point, I was working on all three figures, but the first work in the series is the woman in red trousers and a white top, which is probably the painting I spent the most time on. It’s the most worked in terms of colour and development. Then, it was a question of looking at the three of them together and trying to balance them and whether to bring elements from one work into another.

. . . I think when these women adopt those poses, it represents power and self-determination—probably not what Picasso had in mind.

TJMDid you work from life, from images, or a combination of the two? What is the process of getting the sitters to assume a pose?

CJThe three sitters came and sat for me individually in the studio. I had specific poses I wanted them to adopt based on Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. If you look at Three Women, the sitters’ poses loosely align with how the women in Picasso’s painting appear. But I think that when these women adopt those poses, they represent power and self-determination—probably not what Picasso had in mind. It’s nice to be subverting what I consider to be Picasso’s fear of women and of the so-called “dark continent into an image of women who are completely at home in their skins.

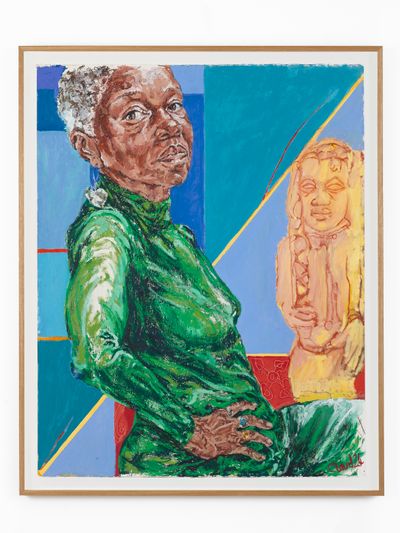

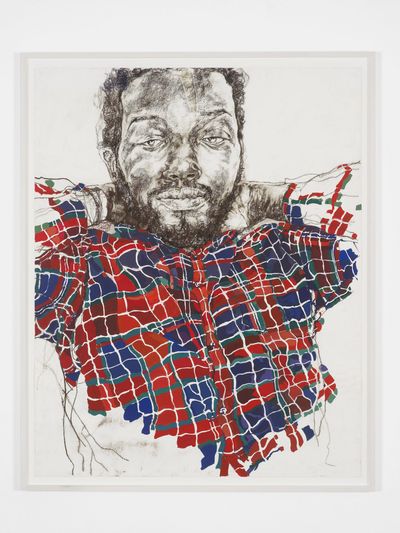

Claudette Johnson, Protection (2024). Oil, oil pastel, and soft pastel on gesso-primed watercolour paper. 154 x 122 cm. © Claudette Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Andy Keate.

TJMWhat’s the atmosphere like in the studio when you’re working? Is there conversation, or do you need silence to get the job done? I understand that in addition to literary and artistic figures, musicians like Thelonius Monk and Charlie Parker have influenced your work. Do you play music while you work, and if so, what’s on your playlist?

CJI don’t have a lot of conversations [with sitters] while I’m working—I can’t talk, draw, and think at the same time—although we do chat in the breaks. Music is important, though; it sets the stage for my work. So, I’ll enter the studio and put on one of my playlists. It feels like it warms up the space, animates it, and then I can make work. I have listened to my playlists so often that I’m almost exhausted with them. I need to make some new ones. I’ve got soul; I’ve got jazz; I’ve got reggae. Naima (1959) by John Coltrane and Miles Davis’ version of ‘Just Squeeze Me’ (1941) are favourites. There’s something so gentle and enveloping about ‘Hope that We Can Be Together Soon’ (1975) by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes that it is often my entry song into the studio.

Exhibition view: Claudette Johnson, Presence, The Courtauld Gallery, London (29 September 2023–14 January 2024). Courtesy The Courtauld Gallery. Photo: © Fergus Carmichael.

TJMI saw an online video made for your Courtauld retrospective Presence. In its first few seconds, the video shows a shot of an inscription on your studio wall just above the skirting. The inscription reads, ‘Just play, Claudette. Do whatever!’ I’m curious to know what play looks like for you.

CJThe artist Lubaina Himid wrote that quote when she visited my studio, and I was having one of those moments where I was thinking, ‘What next?’ and feeling a bit stuck.

So, ‘play’ means not being attached to a particular goal but allowing myself to try things and accept that they might fail while learning something. And I think, especially at this point in my life, it can be quite a challenge to allow myself to do that because there is a lot of demand for the work and a lot of interest. It would be easy to keep on in the same vein. But I want to push myself. I want to try new things. I want to make myself uncomfortable by working with different materials. So, that’s what ‘playing’ means for me: not thinking too much about the audience, but what new journeys I can go on.

Claudette Johnson. Exhibition view: Turner Prize 2024, Tate Britain, London (25 September 2024–16 February 2025). Courtesy Tate. Photo: © Tate Photography/Josh Croll.

TJMThe question of play leads me to your childhood. Was art a big part of your life while growing up in Manchester? Was there much of an inkling that being an artist would be your future?

CJYes, from early on, from the age of five or six, I was doing a lot of drawing. It was always important to me. By the time I was in secondary school, it was what I was known for. There was no one else in the family who was particularly into art. Although my dad drew horses beautifully …

The tutors at Wolverhampton didn’t quite know what to make of me, nor what to do with me.

I had a lot of support from my teachers, particularly in secondary school. The art teachers I had in my late teens transformed things by making the subject so much more exciting. They introduced me to interesting artists like Aubrey Beardsley and Egon Schiele. I remember them encouraging me to study graphic design, and I completed a short placement at a local graphics company when I was 16. But once my tutors at Manchester Polytechnic introduced me to fine art, there was no going back.

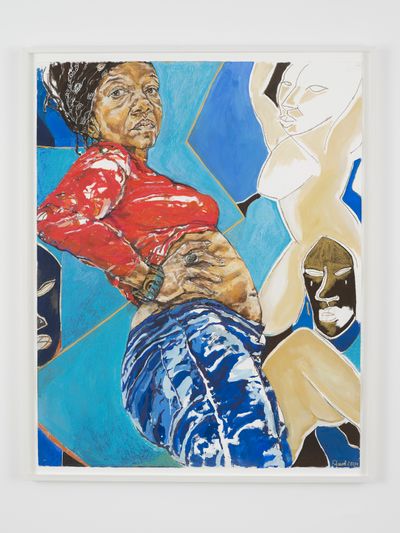

Claudette Johnson, Standing Figure with African Masks (2018). Pastel and gouache on paper. 163 x 132 cm. © Claudette Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Andy Keate.

TJMThese were quite formative moments of contact with art for you, then?

CJThey were. I’ve talked about this before, but a major event for me was when one of my teachers arranged for another student from one of the lower years to sit for me. They just left me to it in a corner of the room, and I can remember how special that felt. That was probably my first experience drawing from life with someone who wasn’t a family member.

TJMWhat was it like studying at Wolverhampton School of Art? You once said the school had a bias towards Abstract Expressionism. How did you square this with your interest in figuration?

CJI felt that my approach didn’t sit very well with their ‘house style’. I’m sure they wouldn’t have called it that, but it seemed that way to me, and all the lead tutors worked in that style. Then again, the student in my year group who was awarded a first for their degree was a fairly traditional portraitist working in oils. So, it can’t have been as rigid as I remember.

The tutors at Wolverhampton didn’t quite know what to make of me, nor what to do with me. Especially as my work became more strident—more abstract and focused on the Black figure. They were interested, but they couldn’t really talk to me about it very much; it just seemed outside of their experience. I remember writing a letter to the college saying, ‘I don’t know if I’m getting enough feedback.’ They arranged for me to have a crit with a Black American poet, the wife of one of the tutors. We had a longish conversation, and she engaged with the work critically, but it wasn’t enough.

Claudette Johnson. Exhibition view: Turner Prize 2024, Tate Britain, London (25 September 2024–16 February 2025). Courtesy Tate. Photo: © Tate Photography/Josh Croll.

TJMTo address this paucity, you went on to join a community of Black artists, the BLK Art Group, with whom you could converse about your work. How did your involvement with them come about?

CJI saw Black Art & Done, the first BLK Art Group exhibition, which was curated by Eddie Chambers for Wolverhampton Art Gallery in 1981. That was my first experience of seeing a show entirely about Black British artists representing themselves and talking about Black experiences in their work. That was exciting for me, and it chimed with what I was doing.

If there was something that could be defined as Black art, what could that do? Could it play an activist role in the struggle?

Eddie, who was only 19 at the time, came to give a talk at Wolverhampton School of Art. Afterwards, he came up to my studio and looked at my work and invited me to join the BLK Art Group, which, at the time, was just him and Keith Piper. I remember meeting Keith Piper initially. I don’t know if Donald [Rodney] was already part of the group then. I can’t remember, but I remember his humour, energy and insight. I believe that a few months later, Wenda Leslie, Janet Vernon and Marlene Smith joined the WYBAs.

Claudette Johnson, Kind of Blue (2020). Gouache, pastel ground, pastel. 121.92 x 152.4 cm. Private collection. © Claudette Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Andy Keate.

TJMHow did the idea come about to host the National Black Art Convention in 1982?

CJThe Black Art Convention came about because we were all talking about being, if not the only Black art student in our year, then one of very few. I was the only one in my year and there was one Black art student in the year above me, and one in the year below. Eddie, Keith, and Donald were in quite an unusual situation at Coventry College of Art, since there were three of them, although Donald was in the year below Eddie and Keith.

We were all bemoaning the fact we were so scattered, and yet, having found each other, we knew we were doing similar things in our work, that we were talking about the same things. That’s how the convention came about: we wanted to get more of us together to see what people were doing. If there was something that could be defined as Black art, what could that do? Could it play an activist role in the struggle?

TJMYour contribution to the convention has become legendary. Can you describe what you presented, and did you anticipate it would be such a major talking point?

CJNo, of course not! There were a lot of speakers that day, and some of them gave very long presentations. My slot was the last one before lunch, like getting the graveyard shift. I presented many slides of my work, as well as slides of work by artists in the Western canon who had included Black figures since Antiquity. I pointed out the differences in approach and feeling regarding how the Black figure was depicted in the work and how women were presented. At some point, someone interrupted me and said, ‘Well, actually, I don’t think you’re doing anything very different from what these white male artists were doing.’ At that point, there was an uproar. After it had all calmed down, we’d run out of time for me to finish my presentation. It had already been agreed that I’d run a women’s workshop later that day, but what happened during my talk precipitated it. Immediately after lunch, anyone who wanted to attend my workshop and hear the end of my talk came to my studio.

TJMWhat did you end up discussing in that breakout workshop?

CJIt was a sharing session. We shared slides of work and talked about what we were doing. I’m not sure that we spent much time expressing frustration about what had happened.I think we were much more interested in and excited by the fact that we’d found each other. However, I did feel frustrated about attendees having to choose between either coming to my workshop or being part of the remainder of the conference in the main lecture theatre, and of course, I felt humiliated that my talk had been curtailed.

Claudette Johnson, Standing Figure (2017). Pastels and masking tape on paper. 159 x 132 cm. Collection Rugby Art Gallery and Museums, Rugby Borough Council.

TJMWhen you look back, how do you feel about the BLK Art Group years and about recounting some of those details?

CJI understand people’s fascination, and it isn’t easy to stick to the facts of what happened and not give in to some of the mythologising that has developed around it. I think we have moved on to some extent with the passing years. I don’t think what happened during my talk would happen now. I certainly don’t think people would’ve let my talk be interrupted that way. I think things have changed in that sense. It’s quite good to revisit it and realise that we’re in a better place now in some ways.

But, also, when I look back at that time, it was a moment of huge change and excitement. We were elated to have a convention of mostly Black art students who had travelled from all over the country. That was just an incredible experience. It’s always nice to remember that.

One of the things I regret is that there’s no documentation beyond the tapes. Someone asked me if I could recall the slides that I showed so that she could try to reproduce the transcript with them, but it’s impossible for me to remember them now.

Exhibition view: Carte de Visite, curated by Lubaina Himid, Helen Cammock, Claudette Johnson, and Ingrid Pollard, Hollybush Gardens, London (4 December 2015–23 January 2016). Courtesy Hollybush Gardens.

TJMThere was a period in the 1990s when things went quiet: you were focused on parenting and were not exhibiting as much or gaining as much attention from galleries, museums, and curators. In the 2010s, you started getting recognition again, along with some of your BLK Art Group peers. What do you think was the catalyst for this renewed interest?

CJThat period in the 1980s, when the BLK Art Group was formed and the convention took place, has been written about and historicized. Because my name comes up repeatedly in those bits of writing, curators and students have been introduced to my work.

One pivotal moment was exhibiting in Carte de Visite, which Lubaina curated at Hollybush Gardens around 2015. Before that, she had invited me to participate in a 2012 show at Tate Britain titled Thin Black Line(s) – a smaller version of an exhibition she had curated at the Institute for Contemporary Arts London in 1985, including Trilogy. Then, some Courtauld students invited me to put work into a show they were curating a year or so later.

I like to have an exit point where there’s a bit of nothing . . . maybe that [harks] back to my interest in modernist artists who were using space in ways that challenged us to think about what we were seeing . . .

So, there were signs of interest, and I think it was just that the work existed again, that there was something to see. It’s impossible to say whether, if I’d produced that work ten or 20 years earlier, it would have taken off in the same way. Someone, in this case, Lubaina, was generous enough and sufficiently committed to my work to extend an invitation to be in the show. She was taking risks because I hadn’t made work for a long time at that point. So, it took someone taking that kind of risk. But the main thing was that the work had to exist.

TJMI know a younger generation has really connected with your work. Ayo Akingbade’s short film Claudette’s Star is a brilliant example of your impact. You also worked for a decade as a lecturer. How did you find teaching and relating to younger generations of artists?

CJI probably taught for longer than a decade because I came to it, then I left, then I came back to it. There were things I enjoyed about it, but I do remember, at times, feeling frustrated that I was watching people grow and I wasn’t making my own work. So, that was not an easy experience. I think maybe, just because of my energy at the time, teaching didn’t seem to be a catalyst for me to make my own work. Instead, somehow, it underlined the fact that I wasn’t making it and didn’t feel I could at that point.

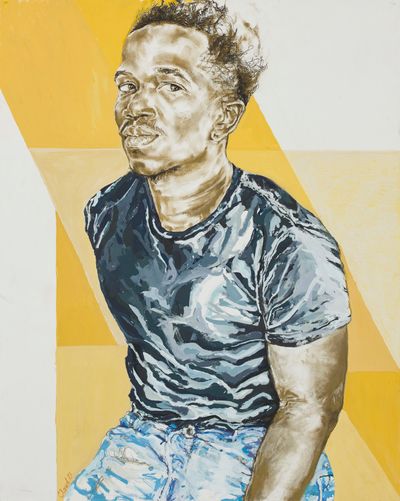

Claudette Johnson, Young Man on Yellow (2021). Gouache and pastel on paper. 152.8 x 122 cm. Private collection. © Claudette Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Andy Keate.

TJMAnd I Have My Own Business in This Skin calls to mind certain strains of modernist painting—Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, mostly—indebted to earlier traditions of European printmaking, the Japanese prints that were circulating widely in 19th-century Europe, and early photography.

A piece like And I Have My Own Business in This Skin has a bold, graphic quality. Its swathes of dense colour and incisive angular lines seem to telegraph some of these art-historical influences.

CJAs a student, I spent most of my second year working in photography, film, sculpture, and printmaking. The photographs I took until I got more proficient were invariably underexposed. I was photographing Black people, so I had to understand how to use more light-sensitive film, at least 400 ASA or higher. This led to more grainy images with higher contrast. I realised that I liked what this did for my subjects. The extreme contrasts in the prints created strong images that were quite raw. This fed into my later paintings. I was experimenting with close cropping, tightly focusing on a particular area of the head or body. I’d started these photographs as research for later work but never used them that way. They were works in their own right.

It’s always a little intimidating breaking into a white space; it takes courage to make those first marks.

TJMFrom early on in your practice, you’ve left figures in various stages of incompleteness or cropped off parts of their bodies. As a viewer, I’m asked to imagine what’s missing or what exists beyond the edges of the images. What draws you to this way of working?

CJIt brings you up close, maybe uncomfortably close. That’s something I’m quite keen to explore. It brings me some kind of aesthetic pleasure to see the shapes created when the figure is cropped or truncated in that way. I allow space to occupy areas where one would expect to find detail. It confounds expectations and gives free rein to my imagination. I can think about what I can do with that space and how to enclose it with line or colour.

I rarely cover every area of the drawing surface. I like to have an exit point where there is absence or breathing space. Maybe that harks back to my interest in modernist artists who used space in ways that challenged us to experience it as something that could be shattered and reconfigured.

Claudette Johnson, Figure with Raised Arms (2017). Gouache on paper. 163 x 132 cm (framed). Courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London.

TJMI’ve noticed small bits of masking tape in some of your pieces.

CJI’m not careful enough in the studio. Sometimes, I’m moving paper or other things around, and the work gets damaged, so I must tape it. In Figure with Raised Arms (2017), that part was damaged, and I just worked over it. But I liked having that damaged area; it’s like an inroad into the drawing. The masking tape on the paper made the first mark for me. It’s always a little intimidating starting work on a pristine sheet of paper; it takes courage to make those first marks.

TJMI hadn’t realised the tape had such a practical function. I thought it was maybe a joke.

CJIt was a way of overcoming the ‘preciousness’ that an artist can feel when approaching a blank sheet of paper or canvas.

TJMWhat are some works of art you’d most like to see in person that you haven’t already?

CJI saw Rembrandt van Rijn’s late self-portraits many decades ago. I’d love to see any of them again and spend a good few hours with them. I think an adolescent part of me is still attracted to Schiele’s graphic line, but I’ve seen very few of his works in person. The scale always strikes me: they’re tiny and so beautiful. The way his line cuts through is inspiring. I’ve just started getting to know the painter Chantal Joffe‘s work. I love the way she handles paint and the feeling I get from the work. I’ve only seen a few of her paintings in person, but I’d love to see more. __I’ve always found the French Post-Impressionist painter Suzanne Valadon quite interesting, too. She often featured women in her work. They’re frank and uncompromising.

TJMFinally, what future projects do you have planned or in the works presently?

CJI shall just be pottering about in my studio, experimenting, making mistakes, and excited and frustrated by what I produce. I am almost never entirely happy with painting. I love the journey of making the work, and each piece is a step towards the always just-out-of-reach image I carry in my head. In each work, I fail better.—[O]

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/claudette-johnson-on-power-and-self-determination/