18 Nov Sandra Mujinga: 'I felt a very urgent need to gather people'

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/sandra-mujinga-on-the-power-of-the-voice/

In Greek mythology, Echo is a loquacious nymph cursed by the goddess Hera for distracting her from the infidelities of Zeus. Driven by retribution, Hera deprives Echo of her own speech and condemns her to repeat the last words uttered by another for eternity. Drawing on the concept of the echo and its counterpart, reverb, in her practice, Congolese Norwegian artist Mujinga most recently occupied and transformed the Kunsthalle Basel for her exhibition, Time as a Shield, flooding it with the thick presence of history.

Mujinga, who also works as a musician, has used sound as a material for several years. In 2022, for IBMSWR: I Build My Skin with Rocks at Hamburger Bahnhof—shown as part of the artist’s Preis der Nationalgalerie presentation—Mujinga made the vast exhibition hall reverberate with an expansive rhythmic drone, reminiscent of a large animal breathing, to accompany a mammoth LED video screen housed in a vast cuboid structure. Her project in Basel saw her expand her approach to collaborate with other vocalists using an ensemble of voices as a metaphor for how the collective protects and empowers the individual. Her intention, she tells me when we met during the exhibition’s run, is to archive and explore ‘the uniquely vulnerable human qualities of voice and expression’.

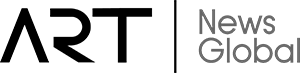

Exhibition view: Sandra Mujinga, Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

Besides sound, the installation at Kunsthalle Basel brought together several of the artist’s abiding interests, including the amalgamation and distortion of portraits through technology and sculptures examining scale, made of diverse fabrics that serve as skins sewn together to produce hybrid creatures.

Ghosts, in particular, are a recurring theme in Mujinga’s practice, whether in titles like Spectral Keepers (2020), in her descriptions of ‘digital ghosts’, or in her use, in Flo (2019), of techniques such as Pepper’s ghost, an illusionary method popularised in the 19th century whereby an image of an object off-stage is projected so that it appears to be in front of the audience. At Kunsthalle Basel, they returned through Ghost Forest 1-7 (2024), a series of steel triangles leaning against the gallery wall conceived of as spectral remnants of trees and a reminder that every physical part of the world leaves behind a trace of its existence.

Sandra Mujinga, Ghost Forest (1–7) (2024). Exhibition view: Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

Mujinga’s ongoing exploration of traces–ghosts being one example–extends to non-human animals: from endangered gorillas in her early moving-image work Humans, On the Other Hand, Lied Easily and Often (2016) to the dinosaur and elephant references of more recent projects, such as Unearthed Leaves (2024) and IBMSWR (2022). The strange, dark animal-human hybrids that populate several of Mujinga’s exhibitions, swathed in fabric and coloured light, intimate something (or someone) beneath their voluminous forms. Often, the figure is too fragmented to cohere into a unified image and, at times, too dark to be entirely visible. They occupy a space between human and nonhuman, reassurance and danger, their indeterminacy frustrating the viewer’s desire to categorise them as a specific entity or potential threat.

Illegibility, the artist reminds us, can be a refuge for those whom the demands of representation in the political-discursive landscape have led to hyper-visibility and overexposure to the controlling mechanisms of surveillance. Unsurprisingly, the technologies and devices through which our worlds are experienced and reflected—mirrors, windows, screens, echoes—have been staples of Mujinga’s work from the outset. For Mujinga, uncertainty, invisibility, and obscurity are forms of protection.

What follows are edited extracts from discussions between Sandra Mujinga and Tendai Mutambu in person and across emails between 3 September and 12 November 2024.

Exhibition view: Sandra Mujinga, Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

TJMFirst, congratulations on your exhibition, Time as a Shield, at Kunsthalle Basel. Can you discuss the conception of the titular installation in the main exhibition hall?

SMTime as a Shield is a sound installation of five sculptural forms made from various new and upcycled fabrics. These forms contain speakers that emit a choir of human voices. This is the first time I’ve placed speakers inside of fabric sculptures.

Sometimes, a single voice can be heard; at others, it might be three or all seven. A voice can emerge simultaneously from two sculptures. Sometimes, you can hear the same voice transitioning from one form to the next, which creates a sense of movement. When all the voices move across the bodies, they echo and reverberate throughout the space.

TJMTime as a Shield intentionally preserves imperfections—silent pauses, the vibrations of human breath. Created using recordings and compositions from seven singers, the work blends solo voices with syncopated moments and hiatuses. What’s the significance of embracing these imperfections?

SMIt all began with the idea of breathing together; if one person’s breath faltered, another would seamlessly take over. I find it fascinating how voices change over time—sometimes, it feels so natural that it seems they’ve always sounded that way. We remember these shifts, but articulating them can be difficult.

One of my inspirations for creating melodies comes from how my mother would ask me for the name of a song, often singing it in a way that was unrecognisable. I vividly recall her rendition of a song by A-ha; she transformed it completely, crafting a new melody in the process.

Another impetus came from how we share much more than just words during telephone conversations; the pauses and breaths convey a sense of presence that adds depth whereas awkward moments can stretch into what seems like an eternity. While working with this, I kept seeing adverts for voice cloning, which has become so prevalent. That inspired me to view myself as an archivist, dedicated to preserving and celebrating the uniquely vulnerable human qualities of voice and expression.

There’s something quite ghostly about the fabrics, having had a life before. I think of them as skins.

TJMHow does your approach to working with sound and music relate to the wider preoccupations in your practice?

SMWhen I entered Kunsthalle Basel’s exhibition spaces, I heard the echo of my footsteps. Everyone said: It’s not a space in which you should ever work with sound. But I thought: I want to work with sound! Every time I met with the institution’s former director, Elena Filipovic, and former curator, Renate Wagner, I thought about the echo and movement.

Later, in a beautiful dialogue with Kunsthalle Basel’s current director, Mohamed Almusibli, we discussed how all the works echoed each other. A lot of my work is about approaching traces of the past through a speculative framework: from science fiction to world building to reworlding.

Before Time as a Shield, I’d mainly been working with electronic music and doing the singing myself, considering my voice to be almost like a sample in a sound library. But for this, I felt a very urgent need to gather people, which translated into thinking about choirs, vocal assembly and creating a new collective body with multiple voices. It’s the same way I approached ‘Shared Breath (1–6)’ (2024) [a series of composite photographic portraits]: I wanted to explore how the collective can offer protection and empowerment to the individual.

Sandra Mujinga, Shared Breath (1–6) (2024). Canson Platine Fibre Rag, Alu-Dibond, lamination on Alu-Dibond, round frame, spacer strip, museum glass, varnish. 64 x 64 x 5.5 cm each. Exhibition view: Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

TJMCan you discuss how you collated the different sounds and the process of working with the choir? Is this something you’re looking to explore further in your practice?

SMIt all began beautifully through collaborating with Mariama Ndure on my performance You Are All You Need (2019) [at Bergen Kunsthall]. After I moved to New York in 2023, Mariama introduced me to the vocalist Shara Lunon, through whom I met Isabel Crespo, Miriam Elhajli, Amirtha Kidambi, and Cleo Reed. Evyn Bileri Banawoye, the main model for ‘Shared Breath’, helped with the casting process since I was still new to the city.

Receiving all the audition videos was truly special, and it led me to discover talents like Jaswiry Morel and Juno Williams. I created folders with melodies to share in advance, but the process ultimately became a call-and-response, with all of us having the freedom to improvise and experiment. The moments I found most magical were during the repetitions, where singing the same melodies over and over slowly revealed something profound in an almost sculptural sense.

I thoroughly enjoyed the process; it was a generous space, especially since it was my first time directing vocalists, and I’m grateful for the support we offered each other. This is definitely an area I want to continue exploring in my practice.

Exhibition view: Sandra Mujinga, Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

TJMYou’ve returned to working with textiles in Time as a Shield, but the forms here differ slightly from your more familiar anthropomorphic pieces, like Spectral Keepers. You’ve also introduced a lot more colour. How are these newer sculptures related to the older work in terms of process and construction, and in what ways do they depart from it?

SMFor Time as a Shield, the forms of the sculptures were influenced by the fabrics I sourced, most of which were donated and upcycled. I’m always trying to find ways of working with old textiles, although I’ve also mixed in some new ones. There’s something quite ghostly about the fabrics, having had a life before. I think of them as skins, and I’m interested in what they conceal and protect and the environments they are hiding from or within.

It’s always an interesting process to have a battle—a push and pull—with the fabrics. There’s another group of sculptures titled Unfold and Repair (2024), currently on show at Pinchuk Art Centre in Kyiv for the Future Generation Art Prize, where I’ve used a similar process of fighting with the fabric by experimenting with draping, sculpting, and even sleeping on them before hand-stitching them.

Sandra Mujinga, Unfold and Repair (2024). Cotton, steel, foam. Courtesy OKNO Studio for PinchukArtCentre/Future Generation Art Prize. Photo: Ela Bialkowska,

This approach was much slower than usual and became quite meditative during the hand-stitching. It’s interesting to smell, stretch, and feel materials to see how they behave and to determine their properties.

For Time as a Shield, I’ve combined lighter fabrics with ones that are heavier than I would usually use to create the effect of sturdy bodies. I think of the lengthy process of draping fabric as freezing time. With the more anthropomorphic figures, like the ones in Seasonal Pulses (2019), I would make a pattern, which I would repeat, and then I’d make another pattern and repeat again.

I began by creating smaller components, such as arms, which I assembled with hoods to become bodies of multiple arms ultimately. This method was clay-like, as the whole was shaped from smaller parts, giving me a sense of freedom. But, with Time as a Shield, the fabrics led the way in the end.

Exhibition view: Sandra Mujinga, Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

TJMYou refer to the fabric sculptures in Time as a Shield as ‘monumental, tree-like sculptures draped in textiles,’ which establishes an image of the natural world at odds with the technological associations implied by the lengths of cable that snake from one sculpture to another and the underlying metallic armature which nods to mechanical affiliations.

SMWith the cables, I was thinking of a forest and how beautiful it is that trees communicate with each other [through an underground network of roots] and how they try to save each other by sharing nutrients. I had in mind the symbiotic relationship between trees and birds. Sometimes, you look at a tree and, though you can’t see birds, you can hear birdsong, as if the tree itself were singing. What I love is that birdsong calms our nervous system because, when birds sing, it’s a way for us to know that everything is safe and going fine. When birds are not singing, that can indicate danger. I imagined trees might then take over the singing, and there was something beautiful and hopeful about that, as trees bear witness to the passage of time—whether it brings climate change or war.

Sandra Mujinga, Shared Breath (1–6) (2024). Canson Platine Fibre Rag, Alu-Dibond, lamination on Alu-Dibond, round frame, spacer strip, museum glass, varnish. 64 x 64 x 5.5 cm each. Exhibition view: Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

TJMLike your earlier photo series ‘LACK’ (2022), ‘Shared Breath’ draws attention to artifice and the technological means through which images are produced and reproduced and manipulated. How did you create these portraits, and what comments do they make on representation, visibility, and surveillance?

SM‘LACK’ consisted of a collage of friends and family, which I made at a time when we couldn’t meet in person because of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions. So, I worked from selfies that I collaged to create new faces. I was thinking a lot about mutual protection.

In ‘LACK’, you can see this distortion and see the different faces. However, with ‘Shared Breath’, the images are a lot more seamless because I worked exclusively with Evyn. They served as a base or a template, and then I would add different facial features on top—many of which were taken from people Evyn introduced me to. It’s a continuation of thinking about Blackness and representation. While I celebrate Blackness in any way I can, I’m also drawn to hiding in plain sight or creating layers where what’s made visible to white-majority institutions is an intentional distortion of some sort.

I’m interested in how, through technology, we willingly and unwillingly share our faces with corporations. My portraits take into account the facial recognition biases that people with darker skin tones experience because so much technology is not tested on or calibrated to darker skin.

Sandra Mujinga, Grief (2024). Exhibition view: Time as a Shield, Kunsthalle Basel (30 August–10 November 2024). Courtesy Kunsthalle Basel. Photo: Philipp Hänger.

TJMGrief (2024) looks similar to some of your earlier works, for example, Spectral Keepers (2020) and Nokturnal Kinship (2018). It features fabric-draped figures in rooms flooded with green light, which you’ve described previously as a stand-in for or an evocation of the green screen. How does this figure and its presentation connect to previous works?

SMGrief was a way to imagine and insist on how irrational and erratic time feels when you’re grieving. You do not exist in linear time; it’s not rational. This was the first time I worked with black fabric on a sculpture. I wanted to visualise the weight of grief while also considering the body as a shadow—something that follows you everywhere. From a distance, the figure appears almost like a silhouette; as you enter the space, you can see the draping more clearly.

The body is massive: its shoulders are more than one metre wide, standing just over three metres tall. I’ve used the same dim green light in other works, so even though the figure is alone in this space, you can think of its kinship to other works before it and the family resemblance it shares with Time as a Shield. It’s like a body on its way to becoming a tree or a body that has been a tree in the past. I wanted it to communicate with previous works while using this newer technique where I mixed heavy fabrics with lighter materials like silk.

Sandra Mujinga, Unearthed Leaves (2024). Steel, fabrics, and wire. 5.9 x 4 x 2 m, 5.4 x 2.8 x 4.6 m, and 4 x 3 x 6 m. Exhibition view: 8th Yokohama Triennale: Wild Grass: Our Lives, Yokohama Museum of Art (15 March–9 June 2024). Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, and The Approach. Photo: Tomita Ryohei, Organizing Committee for Yokohama Trienniale.

TJMIn other work, you’ve torn fabric and then woven it together, a process that shows both fragility and resilience. You used this technique in your piece for this year’s Yokohama Triennial, And My Body Carried All of You (2024). The title suggests an interest in collectivity that’s also present in Time as a Shield and ‘Shared Breath’.

SMThe title evokes carrying a herd or a family and containing multiple histories as a body-bearing witness. In my work, I try to decentre humans—usually by working on a large scale. It’s interesting when we talk about what is threatening [to humans] and what triggers [our mechanisms of] self-defence.

In And My Body Carried All of You (2024) and Unearthed Leaves (2024), I explore the concept of speculative bodies by reflecting on dinosaur fossils. The skins are made from torn fabrics woven back together. As I consider these skins, I’m intrigued by the parallel timelines in which both decay and rebuilding occur. I often think about how unreal it seems that we walk on the same planet these creatures once did. In a time when many species are going extinct, the bodies of dinosaurs—remnants of the past—serve as speculative sites, opening up ways to think about future forms [of life on Earth].

Sandra Mujinga, And My Body Carried All of You (2024). Suspended from the ceiling, consists of steel, fabrics, and wires, measuring 3 x (2.09 x 3.5 x 6.8 m). Exhibition view: 8th Yokohama Triennale: Wild Grass: Our Lives, Yokohama Museum of Art (15 March–9 June 2024). Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, and The Approach. Photo: Tomita Ryohei, Organizing Committee for Yokohama Trienniale.

TJMAnimality and scale were central to IBMSWR: I build my skin with rocks, at Hamburger Bahnhof, which you showed in 2022, and featured an LED video display measuring nine by four metres. What was your thinking behind the main character of that work and the scale at which it was presented?

SMI sometimes like to write a text before I make sculptures or work in different mediums. I did that for IBMSWR: I wrote about a mutated elephant-human, being the last of her kind, living in a dark industrial world. I was thinking a lot about my grandmother, who I never really got to know. She became this character I could write about, and later, I speculated whether she was my grandmother or my future self. This figure moved through the world, bearing witness to all these histories, having to continue living to tell the stories about what she had heard and seen.

One of the main traits this character had to protect herself was to become too big, to expand to the size of a landscape so that she could hide in plain sight. When I was filming, I made it seem as if the main character was going in and out of the giant LED box, disappearing underground, leaving the screen empty and black, and then reappearing as though even that was too small for her.

Exhibition view: Sandra Mujinga, IBMSWR: I Build My Skin with Rocks, Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart (9 December 2022–1 May 2023). © Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, and The Approach. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

TJMI know you draw heavily from literature, especially science fiction as well as works of theory and philosophy, particularly by Black scholars. What were some of the key reference points for IBMSWR?

SMThe title references the Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant’s phrase from Poetic Intention (1969), ‘I build my language with rocks.’ Glissant sought to create a language that, like an island, breaks away from the mainland. In this piece, I envisioned a body that expands through the accumulation of rocks into a landscape while also possessing the potential to crumble.

I also considered architecture to be a living entity, much like the Oankali spaceship in Octavia E. Butler’s science-fiction trilogy Lilith’s Brood (1987–1989). Zakiyyah Iman Jackson’s book Becoming Human (2020) further inspired me to question the concept of Black plasticity, particularly in relation to Catherine Malabou’s ideas on plasticity, which delve into how humanity intersects with Blackness and its relationship to animality within the history of Western science and philosophy. I think having those conversations parallel to insisting on our humanity is important. I’ve always been drawn to thinking about monstrosity—or what is scary in relation to Blackness—as well as to questions of colourism and dark skin.

Exhibition view: Sandra Mujinga, IBMSWR: I Build My Skin with Rocks, Hamburger Bahnhof – Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart (9 December 2022–1 May 2023). © Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, and The Approach. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

TJMIBMSWR has a memorable soundtrack that creates a dramatic atmosphere and mood. How does sound function in this context, and how does it complement or oppose the image?

SMWhen I start producing a soundtrack, I often envision a body with a specific heartbeat—whether it resembles a whale’s heartbeat, which can range from two to ten beats per minute, an elephant’s, at 25 to 30 beats per minute, or our own, at 60 to 100 beats per minute. The soundtrack becomes an anchor, providing a sense of rhythm and time.

I compose tracks in a way that conveys a sense of linear time, allowing listeners to grasp the direction of the experience, while the visual elements consist of repetitions and loops. Typically, I work with the soundtrack and visual material separately; I am drawn to moments of delay and instances where expected synchronization falls short.

I focus on building toward a climax or a reveal in my soundtrack, which contrasts with my visual language. I enjoy crafting an unfolding that then loops, and I find it intriguing to consider how experiencing that climax repeatedly affects our experience.

Sandra Mujinga, Unfold and Repair (2024). Cotton, steel, foam. Courtesy OKNO Studio for PinchukArtCentre/Future Generation Art Prize. Photo: Ela Bialkowska,

TJMCan you tell me about Unfold and Repair?

SMComposed of five, hand-sewn fabrics made of cotton foam and steel, Unfold and Repair delves deeply into the themes of grief and bearing witness. This collection of sculptures is presented at various heights—the shortest being two metres and the tallest being just under three metres—a choice influenced by my experiences of working with vocalists for Time as a Shield. The differing heights symbolise a kind of musical composition, with the human-like figures seeming either to ascend toward the heavens or teeter on the brink of collapse.

I came across the phrase ‘spectacle is not repair’ in Ordinary Notes (2023) by Christina Sharpe, and it resonated with me profoundly. The sculptures in Unfold and Repair explore the notion of suffering bodies rendered as spectacles—whether through entertainment meant to captivate or through the documentation of violence intended to validate experiences. The actions of folding and unfolding become acts of self-preservation. The draping of the fabrics serves to host these transitions, while hand-stitching becomes a daily exercise in making small, intentional decisions, each step informed by the unique qualities of the fabric and the evolving forms of the sculptures.

Through this reflective process, I explore the idea that trauma can serve as a powerful tool for time travel, a concept visually represented by the use of fabric. I aim to capture the delicate balance between vulnerability and resilience. The walls of the space and the light become extensions of the sculptures, unified by the same blue hue.

Sandra Mujinga, Unfold and Repair (2024). Cotton, steel, foam. Courtesy OKNO Studio for PinchukArtCentre/Future Generation Art Prize. Photo: Ela Bialkowska,

TJMWhen and how did you start incorporating textiles into your practice, and has your approach to working with fabric undergone any significant changes over the years?

SMI first started using fabric during my performances as a student at Malmö Art Academy in Malmö around 2010. By 2013, I began creating garments for my videos and textile sculptures, although they were mostly presented as wall works. Five years later, I was commissioned by Max Pitegoff and Calla Henkel to create a performance for Grüner Salon [in Berlin], which I titled Nokturnal Kinship (2018).

I remember studying the choreography of Martha Graham and being intrigued by the idea of devising movement in dialogue with the clothing being worn. Previously, I had made impractical garments that became sculptures, allowing me to explore how clothing could evolve without the [constraints of the] body.

For Nokturnal Kinship, I designed bodysuits, jackets, and trousers with intentionally exaggerated limbs, so that the three performers would have to move slowly through the space, the garments dictating the pace of their movements.

Later, I began to envision what a mannequin to host these garments might look like. This led me to conceptualise these structures as skeletons in wearable sculptures and, ultimately, to my first presentation of human-like figures during my 2018 solo exhibition, Calluses, at Tranen [in Copenhagen].

I have often thought about the relationship our bodies have to garments—like when you wear shoes that are too small or a jacket that’s too long, but you make it work. The dialogue between your body and this external skin presented to the world is fascinating to me. It’s as if the garment has its own life, and you must dance with it or come to an agreement with it. Those moments inspire my sculptures. —[O]

Time as a Shield was shown at Kunsthalle Basel from 30 August to 10 November 2024. Sandra Mujinga’s current solo exhibition, Fleeting Home, is on view at the Museum der Bildenden Künste, Leipzig from 30 November 2023 to 29 December 2024. A solo presentation of Mujinga’s work will open at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam from 13 September 2025 to 11 January 2026.

Source Credit: Content and images from Ocula Magazine. Read the original article - https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/sandra-mujinga-on-the-power-of-the-voice/